Bulson, Eric Jon. Ulysses by Numbers. Columbia University Press, 2020. cuny-gc.primo.exlibrisgroup.com, https://doi.org/10.7312/buls18604.

Summary: Eric Bulson employs a quantitative and computational approach to analyze the novel “Ulysses” by James Joyce. His objective is to gain insights into the novel’s structure and themes through the application of statistical methods. By examining the repetitions and variations of numerical patterns within the text, Bulson aims to uncover a deeper understanding of the novel.

My experience: It was an interesting, but challenging read for me. I did skim through the “Ulysses” by Joyce on multiple occasions, but I never fully immersed myself in its pages. Now, I’m feeling more open to giving it a try at some point in the future. Having that in mind, I mostly focused on understanding the method Bulson used to convey his message.

Eric Bulson is a professor of English at Claremont Graduate University. He got his PhD in English and Comparative Literature from Columbia University. His research interests goes on a range of subjects including Modernism, Critical Theory, Media Studies, World Literature, Visual Storytelling, and British and Anglophone Literature from 1850 to 2000.

Ulysses by Numbers highlights the presence of numeric patterns throughout “Ulysses,” asserting their role in shaping the novel’s structure, pace, and rhythmic flow of the plot. He suggests that Joyce’s deliberate use of numbers is purposeful, enabling him to transform the narrative of a single day into a substantial piece of artwork. Bulson explores the intentionality behind Joyce’s numerical choices, emphasizing how they contribute to the book’s richness and complexity. Additionally, the tone of Bulson’s analysis combines elements of playfulness and exploration, adding an engaging dimension to the discussion.

He emphasizes he will be focused on the “use numbers as a primary means for interpretation“, to make the point that a quantitative analysis is the missing point to compose a “close reading as a critical practice”. He proposed it as an additional method to the traditional literature review that focused on the text.

“Once you begin to see the numbers, then you are in a position to consider how it is a work of art, something made by a human being at a moment in history that continues to recede into the past. We’ll never get back to 1922, but by taking the measurements now, we are able to assemble a set of facts about its dimensions that can then be used to consider the singularity of Ulysses and help explain how it ended up one way and not another.”

Bulson recognizes that literature critique based on computational methods is still under development, and not quite popular yet. The utilization of computers in literary analysis is a relatively modern phenomenon, considering that the majority of such processes were conducted manually until a few centuries ago. The practice of using numbers to elaborate narratives was common until the 18th century in the work of Homer, Catullus, Dante, Shakespeare, and others. However, the rationalism of the upcoming area covered up this practice. Only in the 1960s did the search for symmetry and numerological analysis reemerged, culminating in the method of computational literary analysis (CLA).

Bulson explains that he differs from the usual approach to adapt the use of small numbers in his analysis. Firstly, his analysis is based on samples. It means that instead of analyzing the entire novel the author selects specific sections. Secondly, he recognizes that he applies basic statistical analysis. Despite the simplicity of his analysis, his goal is to make literature more visible.

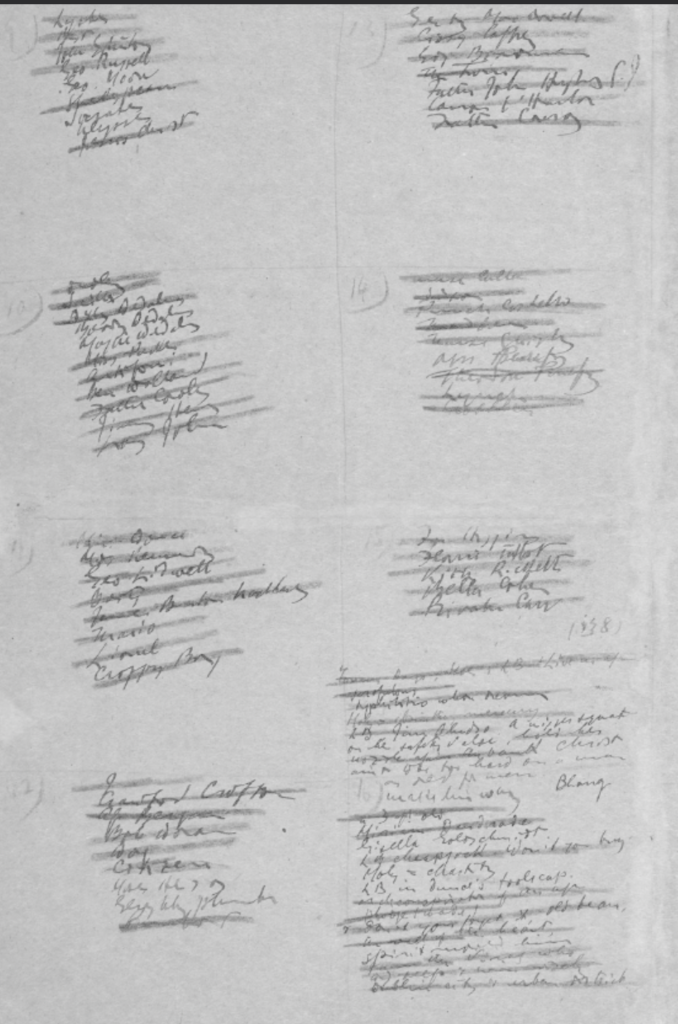

In terms of sources, he goes deep into finding the sources of data he considered in this analysis:

“Measuring the length of the serial Ulysses, simple as it sounds, is not such a straightforward exercise. In the process of trying to figure this out, I considered three possibilities: the pages of typescript (sent by Joyce to Ezra Pound and distributed to Margaret Anderson, editor and publisher of the Little Review, in the United States), the pages of the fair copy manuscript (drafted by Joyce between 1918 and 1920 and sold to the lawyer and collector John Quinn), and the printed pages of the episodes in the Little Review (averaging sixty-four per issue).”

It’s interesting to notice how he illustrates his arguments with both handwriting and drawings with graphs and charts, which encompasses the idea of a craftwork mixed with technological visualizations.

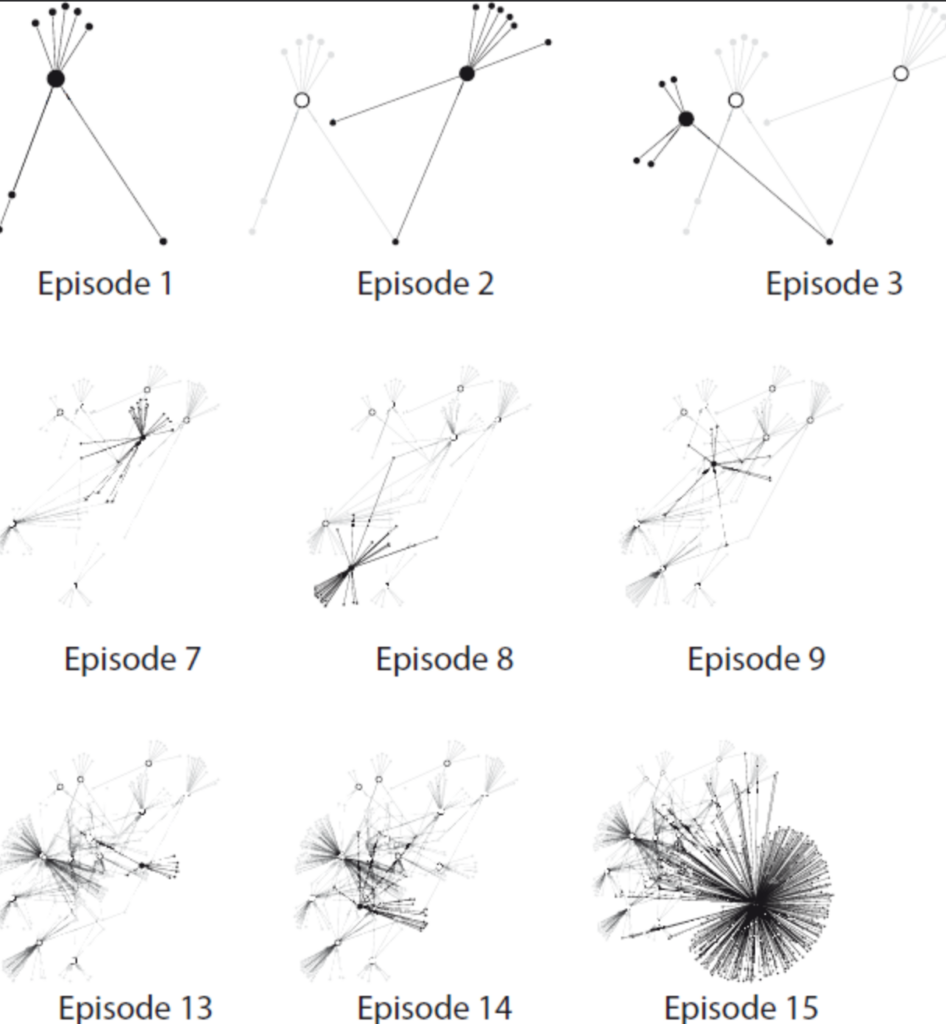

In terms of the novel’s structure, Bulson examines the presence of 2’s and 12’s, such as the address “12, rue de l’Odéon” and the year of publication (1922), among other recurring patterns. Additionally, he delves into the number of paragraphs and words in the text, and explores the connections between them. Through one particular analysis, he determines the level of connectivity among the chapters, identifying Chapter 15 as having the highest number of nodes and being the most connected to other chapters, which he refers to as an “Episode.” Chapter 15 consists of 38,020 words and 359 paragraphs. Another significant episode is Chapter 18, which contains the second-highest number of words (22,306) but is condensed into only 8 paragraphs. Chapter 11, on the other hand, has the second-highest number of paragraphs (376) and comprises 11,439 words.

Bulson also examines characters from a quantitative perspective, contrasting the relatively small number of character count in “Ulysses” with other epic works such as “The Odyssey” or “The Iliad.” He uses a visual representation of a network to enhance the understanding of the novel’s scale and structure – highlighting the crowded number of roles in episode 15.

“Episode 15 arrived with more than 445 total characters, 349 of them unique. If you remove the nodes and edges of episode 15 from the network, Ulysses gets a whole lot simpler . That unwieldy cluster of 592 total nodes whittles down to 235 (counting through episode 14). Not only is a Ulysses stripped of episode 15 significantly smaller: it corresponds with a radically different conception of character for the novel as a whole”.

Moving from the text meta analysis, the authors examine who read the 1922 printed book. Outside of Europe and North America, only Argentina and Australia. In the US, the book was most popular in the West Coast. In the following chapter, he tries to answer when Ulysses was written. He mentioned that the traditional answer is that Joyce began writing the novel in 1914 and finished it in 1921. However, he points out that this is such a simplistic answer. He argues about the nonlinearity of the written process, more fluid and organic, and less structured.

In the final chapter, the author goes back to the content analysis, bringing a reflection that could retreat himself “after reducing Ulysses to so many sums, ratios, totals, and percentages, it’s only fair to end with some reflection on the other inescapable truth that literary numbers bring: the miscounts”. He refers as “miscounts” any bias or issues in terms of data collection of analysis.However, he defends the method by saying that literary criticism is not a hard science, and imprecisions, vagueness and inaccuracy is actually part of the process. Also, theories based on small samples are popular in historical and social analysis, and his work should not be discredited because of that.

“Coming up against miscounts has taught me something else. Far from being an unwelcome element in the process, the miscounts are the expression of an imprecision, vagueness, and inaccuracy that belongs both to the literary object and to literary history. In saying that, you probably don’t need to be reminded that literary criticism is not a hard science with the empirical as its goal, and critics do not need to measure the value of their arguments against the catalogue of facts that they can, or cannot, collect.”

After reviewing the contribution of his perspective, he concludes that “readers might to bridge the gap, Ulysses will remain a work in progress, a novel left behind for other generations to finish. Reading by numbers is one way to recover some of the mystery behind the creative process.”